Two Septembers ago, the Roman Empire broke the Internet. A cascade of clips went viral over several weeks in which women asked their boyfriends and husbands how often they think about the Land of Romulus & Remus. The answers, to their surprise, in many cases ranged from once a week to once a day. Such frequency probably says more about the peculiar fantasies of the male psyche than anything. But in their defense, the men took pains to point out Rome’s real enduring legacy, from legal codes to architectural design to multiple living languages.

Today’s obsession with Rome stands in continuity with every age since the sun set on the Eternal City. Almost all subsequent Western imperiums have modeled themselves on Rome, from Charlemagne to Napoleon. The United States is no different. The founding generation consciously looked to Res Publica Romana as they laid the foundation for the American Republic. Our governing institutions (the Senate); emblems (the eagle); mottos (“E Pluribus Unum”); and buildings (the Capitol) were all taken from the Laureled State, as was the founders’ idea of civic virtue. George Washington famously imitated the Roman hero Cincinnatus when he stepped down from the presidency.

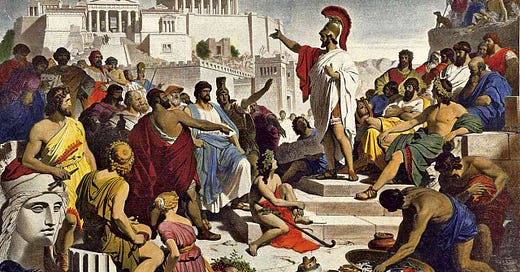

The appeal of Rome is strong. And who could deny it? Its military was unmatched. Its boundaries stretched from Britain to Palestine. Its state endured for over twelve centuries, twenty-two if we include Byzantium. It seems the natural choice to emulate when trying to achieve collective greatness, whether in 1776 or today. And yet, that choice is wrong. None of us, men or women, should be thinking about the Roman Empire—certainly not as we contemplate how to get America back on track. We should instead be thinking about the republic that Rome itself imitated and eventually conquered: ancient Greece. To be precise, the city-state of Athens.

The Flowering of Athens

Athens was greater than Rome by every measure—and it’s not even close. During the two centuries of its democracy (508—338 BCE), this tiny polis produced a cultural and economic efflorescence unequaled in European history. At its height, its military exercised hegemony across the Aegean world. What’s more, an array of seminal Athenians laid the foundations of Western art, science, and mathematics; drama, history, and philosophy. As historian C.E. Robinson put it,

This handful of men attempted more and achieved more in a wider array of fields than any nation great or small has ever attempted or achieved in a similar space of time.

Rome’s feared legions? They were based on the hoplite warfare pioneered by Athens. Rome’s marbled columns and buildings? Derived from the temples the Greeks built in Italy & Sicily. The Aeneid, Rome’s national epic? Virgil aped The Iliad & The Odyssey to the point of plagiarism. Even Rome’s gods were copies of Greek deities. The Athenian playwrights, philosophers, and historians are prized today; with few exceptions, Rome’s are forgotten. Case in point, English director Robert Icke just staged a major production of Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex in London. When was the last time you saw a Roman play?

In raw economic terms, Greece bested Rome, too. According to Josiah Ober’s The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece, during its democracy Athens’s population grew by a factor of twenty-five, its household goods by a factor of ten. It had a per capita annual population growth rate of 0.2%, double that of Rome’s. 32% of Athenians were urban-dwellers. Romans? Just 10%. To put this into perspective, Europe did not again achieve Athens’s level of urbanization until the Dutch Republic in the 17th century. (England didn’t get there until the early 19th.) And in terms of broad prosperity, the numbers are even more striking: Athens was able to move some 58% of its population into the middle class, with the other 41% remaining at subsistence level (and 1% in the elite). Rome’s middle class, by contrast, stood at just 12%, with 86% of its populace mired in deep poverty.

How did Athens do it? Was it just blessed with superior minds? Ober says otherwise.

He traces the branches of its efflorescence to the root, diagraming its evolution:

The economic and cultural boom was built on a prior layer of specialization; exchange of goods & services; education; and mobility.

This layer in turn stood on a layer of capital investment in human, social, and material resources; low transaction costs; innovation in technology & institutions; and rational cooperation.

This layer itself turned on the polis’s fair rules and citizen-centered state.

And this layer, finally, was derived from a natural foundation: human beings’ capacity for decentralized cooperation.

His conclusion is profound: Greece was great because of a cultural accomplishment that was supported by sustained economic growth. That growth, in turn, was made possible by its democratic approach to politics, which fit human nature. Rome, even in its republican era, was never democratic; its aristocracy dominated the Senate. The arc of Rome ran from monarchy to oligarchy to autocracy. Athens, by contrast, went from oligarchy to democracy, before falling to the autocracy of Macedon. Its efflorescence followed that same trajectory, rising and falling with its democracy. The lesson is clear: If America truly wants to be great, we should discard our Roman trappings and reinvent ourselves as the new Athens.

Anatomy of Democracy

What, then, was the nature of the Athenian regime? How did its democracy function? Most people, if they think about Athens at all, vaguely remember that it was a direct democracy—its Ecclesia, or Assembly, allowed any citizen to participate first-hand in the decisions of the state. There’s some truth to this; Athens did have an Assembly, which met about forty times a year and was open to all citizens. If you could get a seat in time, you could participate in its debates and votes.

But in many respects, this image is wrong. The Assembly actually dated from Athens’s oligarchic era; the emergent democracy broke with its practices in core ways. The democracy wasn’t, in fact, direct—it used representation in its key institutions. And unlike the Assembly, where a small group of rhetoricians dominated the debates, the democratic bodies featured structured, rational deliberation among a broad swath of delegates.

In fact, the depth, breadth, and sophistication of the polis’s governing institutions puts those of modern states to shame. Historian C.L.R. James says it best in his essay “Every Cook Can Govern” from 1956:

We must get rid of the idea that there was anything primitive in the organization of the government of Athens. On the contrary, it was a miracle of democratic procedure.

I invite you, then, to hop in my time machine and take a tour of ancient Athens.

Athens at a Glance

The city-state of Athens consisted of an urban center and surrounding environs—in terms of size and rural-urban split, it was comparable to Rhode Island. Like America, Athens was riven with divisions. Geographically, it was made up of city dwellers (artisans), coastal dwellers (fishermen), and mountain dwellers (goatherds). Demographically, it boasted a population of some 300,000, of which 50,000 were free men; 50,000 free women; 50,000 immigrants (or “metics”); and 150,000 enslaved laborers.

Let’s address one inconvenient fact head on: Athens’s illiberalism. Bring up Greece today, and sooner or later you’ll hear from someone about Athens’s vast slave population and how, even among its free inhabitants, it limited citizenship to men. Women and immigrants were simply not part of the body politic. This is true. In this respect, modern liberal states—with their broad granting of rights and suffrage—are more democratic than Athens. Yet it took them centuries to get there, we must recall, with the U.S. granting full citizenship to African Americans only sixty years ago. And now, in 2025, we’re witnessing dangerous backsliding on this front at home and abroad.

In its sexism, xenophobia, and slave labor—not to mention its brutal imperial wars—Athens was authoritarian. And to its own detriment. By foreclosing the vast majority of its populace from the political process, the polis curtailed its knowledge base, cut off innovation, and stunted economic growth. Far from being the basis of Athenian democracy (by supposedly allowing free citizens the time to engage in affairs of the state), Greek slavery—like American—directly undermined government by the people. What’s more, such repressive social arrangements betrayed the republic’s core values: freedom, equality, and the common good. As in the United States, Athens’s fathers knew this, and knew they had no excuse, except their own bigotry.

It should go without saying, then, that we mustn’t emulate Athens in these respects. But in many other respects, we should. The Greeks didn’t invent democracy. Yet when it came to its free males, Athens placed political power in the hands of everyday citizens more than any regime in the past two and a half millennia. Those citizens were themselves divided along class lines. At the top were some 1,000 aristocrats, men from landed patrician families. Below them was a layer of farmers & artisans (zeugitai) numbering some 35,000. At bottom were day laborers (thetes), about 25,000. For generations, the city-state was ruled by an aristocratic oligarchy. Within the Areopagus, their main institution, landed elites used elections to maintain power, locking out the working classes.

The result should sound familiar to contemporary ears: the rich grew richer while the poor grew poorer. As social inequities ballooned, the masses became increasingly angry and resentful. The aristocrats attempted to remedy the situation in 594 with the reforms of Solon, but these failed to address the lack of distributive justice at the root of society. Eventually, a populist demagogue named Peisistratus—a member of the elite—exploited the people’s grievances and rode them to power in a coup d'état. His tyranny lasted twenty years; upon his death, rule passed to two feckless sons, Hippias & Hipparchus. When the latter was assassinated in 514, his brother led a bloody purge, sparking a palace coup by the aristocrats and the intervention of Sparta.

This combination drove Hippias from the city. But the situation soon degenerated into civil war over how to fill the power vacuum. On one side stood an elite named Isagoras, backed by the aristocracy. On the other, an elite named Cleisthenes, backed by the Demos—the People. Things went badly for Cleisthenes at first; in 509, he and his lieutenants had to flee Athens. But in his absence, the Demos revolted against their oligarchic masters, driving Isagoras out. Cleisthenes returned triumphant, and—under the direction of the Demos—he put in place the pillars of a new democratic regime. Let’s look at each in turn.

The Council of 500

Cleisthenes’s first move amounted to social engineering: he divided the city-state into 139 new wards (demes) to promote local self-government. He also took aim at the geographic and cultural divisions afflicting Athens, reorganizing the polis into ten artificial tribes. Citizens were assigned a tribe at random, with one-third of each tribe’s members coming from the coast, one-third from the mountains, and one-third from the city. Such intentional mixing overcame the siloes the men inhabited, forging bonds of trust and promoting civic unity. In fact, these tribes constituted the political and military basis for the entire regime, as the men served in war and government as a tribal cohort.

After this, Cleisthenes laid down a new democratic institution: the Council of 500. This Council, true to its name, was made up of fifty citizens from each of the ten tribes. Councilors held office for one year (yes, one) and could serve just twice in their life (not consecutively). Operationally, the Council combined legislative, judicial, and executive functions. It could issue decrees, engage in foreign policy, conduct trials of official misconduct, and prepare agenda items for the Assembly. Each group of fifty members served on the Executive Board for a month, the presidency of which rotated every twenty-four hours.

More revolutionary than that, though, was how the Council’s members were picked—not by election, but by sortition. That’s right: the key change the Athenians made to establish democracy was to move away from elected politicians and instead choose everyday citizens by lot. As is true now, elections in ancient Greece were dominated by elites; sortition circumvented the web of nepotism and patronage that’s a feature, not a bug, of electoral systems. The Athenians even invented an ingenious machine, the kleroterion, to conduct random selection in the Agora. The blind draw was both inherently democratic—it guaranteed equal opportunity—and also prevented power-hungry people from capturing the system. In fact, it was the anti-corruption properties of sortition that held its greatest appeal. Because, also like now, professional politicians in ancient Athens had a penchant for abusing their office and lining their own pockets. Which brings up the judiciary.

The People’s Court

The People’s Court was the regime’s chief democratic organ. Unlike our judicial system, its express purpose was to prosecute officials for political crimes: serious misconduct, unconstitutional proposals, and abuse of power. Also unlike our system, the Courts had no professional judges. All trials were conducted by a jury of everyday citizens, numbering from 501 up to 2,001. Jurors were selected from an annual standing pool of some 6,000, who were paid, subjected to basic scrutiny, and bound by oath. The defendant and his accuser squared off in the trials, which featured witnesses and evidence, and lasted (once again) just one day. Upon completion (and without deliberating), the jurors voted by secret ballot, with a simple majority needed to convict.

Sentences were proposed by both parties, with the jury voting to accept one. These usually amounted to fines, which could also be levied against an accuser if he failed to achieve a minimum of guilty votes (to prevent frivolous accusations). Serious offenses, however, were punished by stripping the guilty party of citizenship or even banishing him from the polis for a decade. The latter, known as ostracism, was used sparingly (perhaps a mere fifteen times in two centuries) but, like a cop on the beat, it deterred would-be tyrants and oligarchs among the elite. Exile may seem harsh at first blush, but considering the graft and malfeasance of our time, it might deserve a second look.

Magistrates

While not having a bureaucracy in the modern sense, the Athenian regime counted on some 700 magistrates to run the state. There were over seventy different types, ranging from civil (inspectors of buildings, roads, waterworks, etc.) to religious (keepers of the cults and sanctuaries) to financial. As with the Council, the term of office was just one year. No citizen could occupy the same office more than once, and there was a cooling off period of one year before being eligible to serve in any other magistracy. Of the 700 posts, 600 were assigned by lot, while the remaining 100—the generals—were elected. Like jurors, magistrates were scrutinized and bound by an oath.

Legislative Juries

Athenian democracy wasn’t born perfect. The polis improved and adapted it over the years to address flaws and combat corrupting influences. The greatest reforms took place in 403, after the democracy was briefly overthrown by tyrants and oligarchs. Democrats witnessed over the previous decade how the Assembly had been swayed by demagogues to invade Sicily. The expedition met with grief, a disaster that precipitated the toppling of the regime.

Once they wrested back power, the democrats reallocated much of the Assembly’s power to new legislative juries. These panels—ranging from 501 to 1,001 to 1,501 citizens—were drawn from the same annual pool of 6,000. But instead of trying a person, they tried an idea. Any statutory proposal put forth in the Assembly was now sent to a jury, where the advocate had make his case, opposed by five other citizens. Trials lasted one day, and a simple majority decided the outcome. From 403 until the fall of the polis in 338, these legislative juries represented the apex of Athenian democracy.

Executive Leadership

At this point you might be asking yourself, “Ok, but who’s in charge here? Where’s the boss?” The answer is, really, no one. Contrary to most modern polities, Athens did not have a central executive. There was no president or prime minister or even a dual consulship (as in Rome). It was a boss-free regime. Or more to the point, the people were their own boss. This isn’t to say that there were no political leaders in Athens, quite the opposite. The polis cultivated orators and statesmen from the ranks of the elite, and these men exercised significant influence. Generals held great importance, an office the Athenians reserved for prominent men via elections. The most famous leader of all, of course, was Pericles; he was elected general repeatedly for years and guided the polis through the early phase of the Peloponnesian Wars.

But the authority that these leaders enjoyed was mostly soft and informal; the Council, the Assembly, and the Courts were the real locus of power. Even Pericles served at the pleasure of the Assembly, which could (and did) withdraw its support when his performance slipped. While providing a role for talented individuals, the democracy resisted the temptation to aggrandize their control. In fact, it was precisely when the Assembly fell under the spell of charismatic personalities in the late 4th century that things went off the rails and temporarily reverted to tyranny. The Athenian efflorescence was a collective achievement of everyday citizens—not (contrary to current ersatz philosophies) some omnipotent CEO.

From Athens to America

By now you can appreciate the sheer scale and complexity of Athenian democracy. Flawed, ever under threat, it had its share of failures. Nonetheless, it achieved profound results. It did so because it was animated by a fundamentally different premise than modern electoral republics. Liberalism, which undergirds those systems, holds that while the people are sovereign, they must surrender self-government to a separate class of rulers. Elections are the ritual where this outsourcing occurs—it’s no coincidence that elect and elite derive from the same etymological root. In voting for representatives, we consent to be lorded over by a set of superiors, who are empowered to rule any way they like—and we may not.

Athenian democracy was founded on a radically distinct theory: that citizens rule and be ruled in turn. Rather than submit to governors, the people should govern themselves. In this respect, Athens was superior to modern liberalism. Sortition and rotation enabled such citizen-rule at scale. It ensured that power stayed in the hands of everyday people, while at the same time not requiring every, or even most, citizens to participate in state matters all the time. Nonetheless, over the years a huge number of Athenian citizens took part in the political institutions. In a span of three decades, a quarter to a third of them served on the Council of 500, and almost everyone sat on a jury of some kind at least once. Combined with the local governance of the demes, this amounts to an extraordinary exercise in mass empowerment.

It was this bottom-up system—grounded in sortition—that enabled Athens to defeat top-down Persia, catalyze its economy, and fire a cultural explosion that influences us to this day. Aristotle, who witnessed this first-hand, said it best in Politics:

The appointment of magistrates by lot is democratical, and the election is oligarchical.

Never has so much turned on so short a phrase. As Americans seek to build a new house of our republic, we’d do well to shift our gaze from Rome to Greece and study the Athenian blueprint.

References

Mogens Herman Hansen, The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes (1999)

Bernard Manin, The Principles of Representative Government (1995)

Thomas N. Mitchell, Athens: A History of the World’s First Democracy (2019)

Josiah Ober, The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece (2015)

Josiah Ober, Demopolis: Democracy Before Liberalism (2017)

So interesting to consider the journey of Athenian democracy vs Roman rule. Thank you for this good read and important for our times!

Nick, this is the best concise account of the Athenian breakthrough, how Assembly by lot was a key foundation for the exceptional performance of the Athenian state. The citizenship and assembly was only made up of Athenian citizens who ruled a network of city states by force and didn't cede the same local governance to its regions. Imagine how much more intelligence, wisdom and knowhow we could tap into and channel where this same kind of system is supported by technology and spread to every neighborhood, town and state....